Steampunk Cowboy Level Blockout

Description: This level began as my final assignment for Emilia Schatz’s Level Design for Games course. After the class’s conclusion, I spent additional time expanding upon and iterating on the space. The level takes the cowboy protagonist through two exploration spaces ( a town and an abandoned mine) as well as two combat spaces (a fort and a desperado camp).

Platforms: PC

Team: none (solo project)

Type: Academic Project (CGMA Level Design for Games class)

Role: Level Designer

Core Responsibilities: Level layout consisting of multiple combat and exploration spaces (Character/enemy models, controller, enemy AI scripts, and some of the smaller props provided as part of the course).

Tools: Unity, Maya

Available for Download Here

Premise and Gameplay Video

Level Premise (as provided by Emilia Schatz): Many years ago the cowboy’s mother was a prospector. She struck it rich. Unfortunately, her partner betrayed her and stole the gold for himself. The cowboy’s mother tracked him down, but he died before she could find out where he stored the gold. Recently though, the cowboy happened upon clues to the gold’s location, but his sworn enemy overheard the plans to find it and has arrived with an army of deparados. They’ll do anything to keep the cowboy from his rightful treasure.

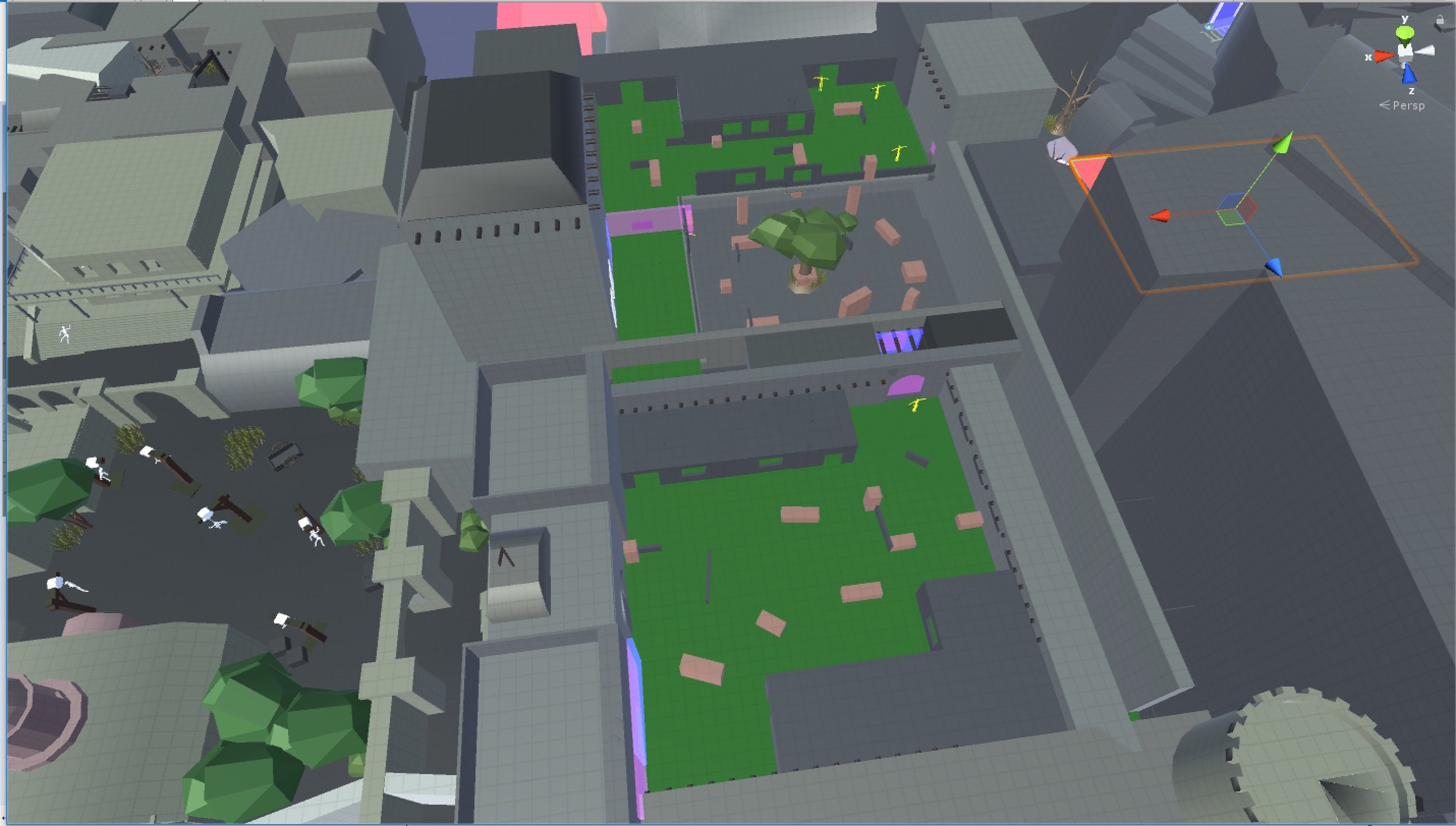

Level Overview

as part of the assignment, Emilia outlined the flow of the level that she wanted us to adhere to. The level features 2 exploration areas, and two combat areas (the first consisting of a smaller encounter and the second a larger one) before reaching the treasure. The assignment also required us to include a valve before each of the combat spaces. A valve is essentially an obstacle that prevents the player from backtracking through the level after they pass it.

From the course, I learned about the utility of Valves. Valves are used for a variety of reasons including technical considerations (they present a good time for parts of the level to be loaded and unloaded from memory), they prevent potentially awkward encounters (luring enemies backwards through the level to spaces that aren’t intended for combat), and they also provide focus for the player’s possibility space (this is especially useful for puzzles, i.e. the player won’t backtrack through the level looking for a solution that isn’t there).

Story Values and Shape Language

In Emilia’s class, she discussed adapting screenwriting guru Robert McKee’s concept of story values to level design. In his book, “Story,” McKee defines story values as “the universal values of human experience that may shift from positive to negative, or negative to positive, from one moment to the next.” For a story to be interesting, it needs to gradually (and nonlinearly) shift between two opposing values (e.g. light to dark, life to death, vulnerability to empowerment, etc.)

Emilia taught that the actual level geometry can and should mirror the values expressed in the game’s story to better convey the overall narrative.

Below are examples of how I used shape language to mirror the narrative of the level:

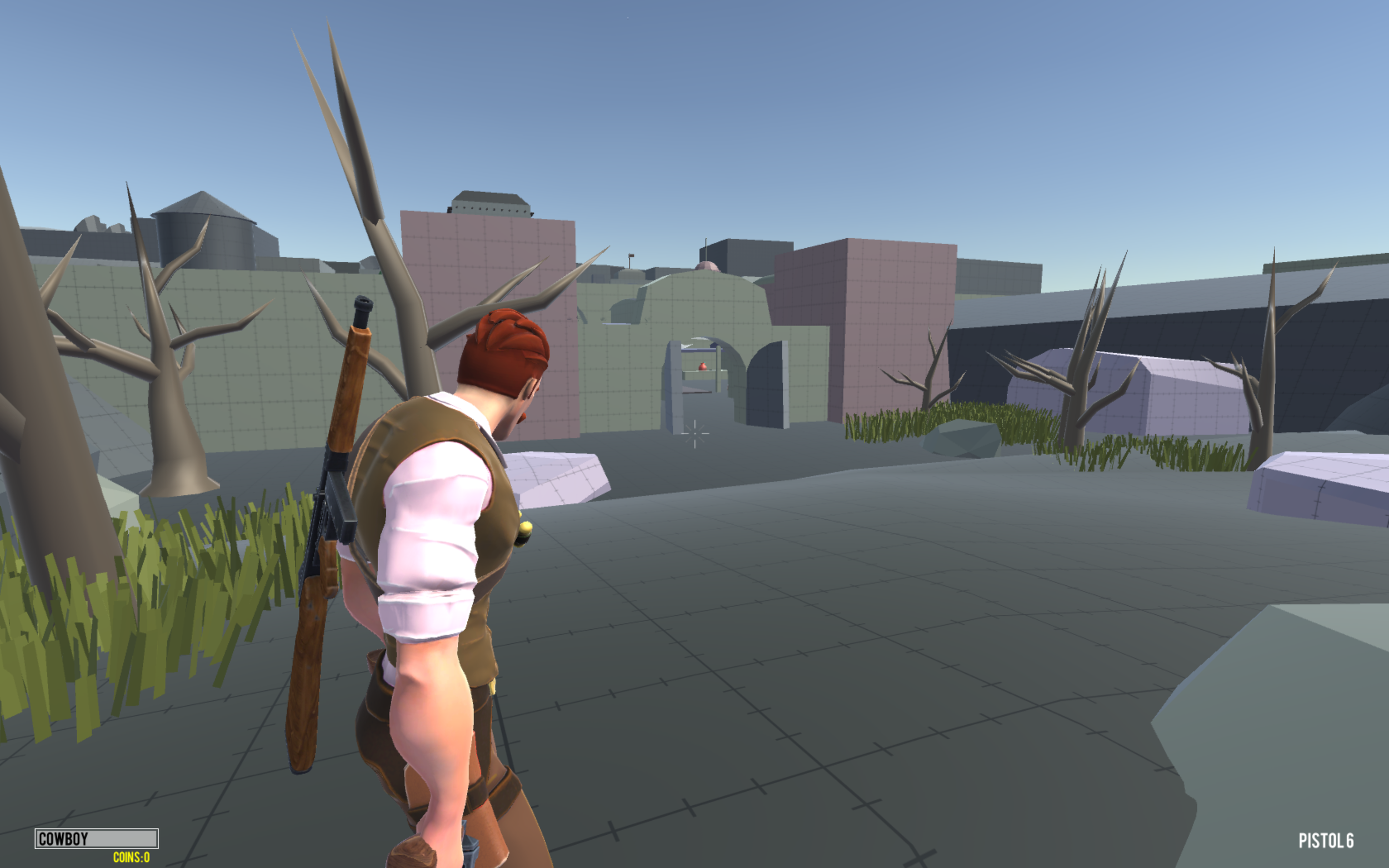

Story Context: This is the first scene at the beginning of the level. The cowboy character is in high spirits and feels determined as he sets out on his adventure with the intent of retrieving his mother’s lost treasure.

Shape Language:

The landscape is made out of gentle, rounded hills communicated a safe, welcoming environment. This isn’t a place for the player to be on guard.

The rounded gate archway beckons the player toward it.

The rest of the city consists of rectilinear shapes creating a contrast between the man-made structure of the city and the surrounding frontier.

The sharp, pointed trees act as “bumpers” guiding the player toward their goal and subtly encouraging them not to stray off.

There aren’t many objects of interest in the space outside the city and the path to the gates is clear and unoccluded. This draws the player toward their goal and discourages lingering in the area. This ties to the character’s determined/driven emotional state.

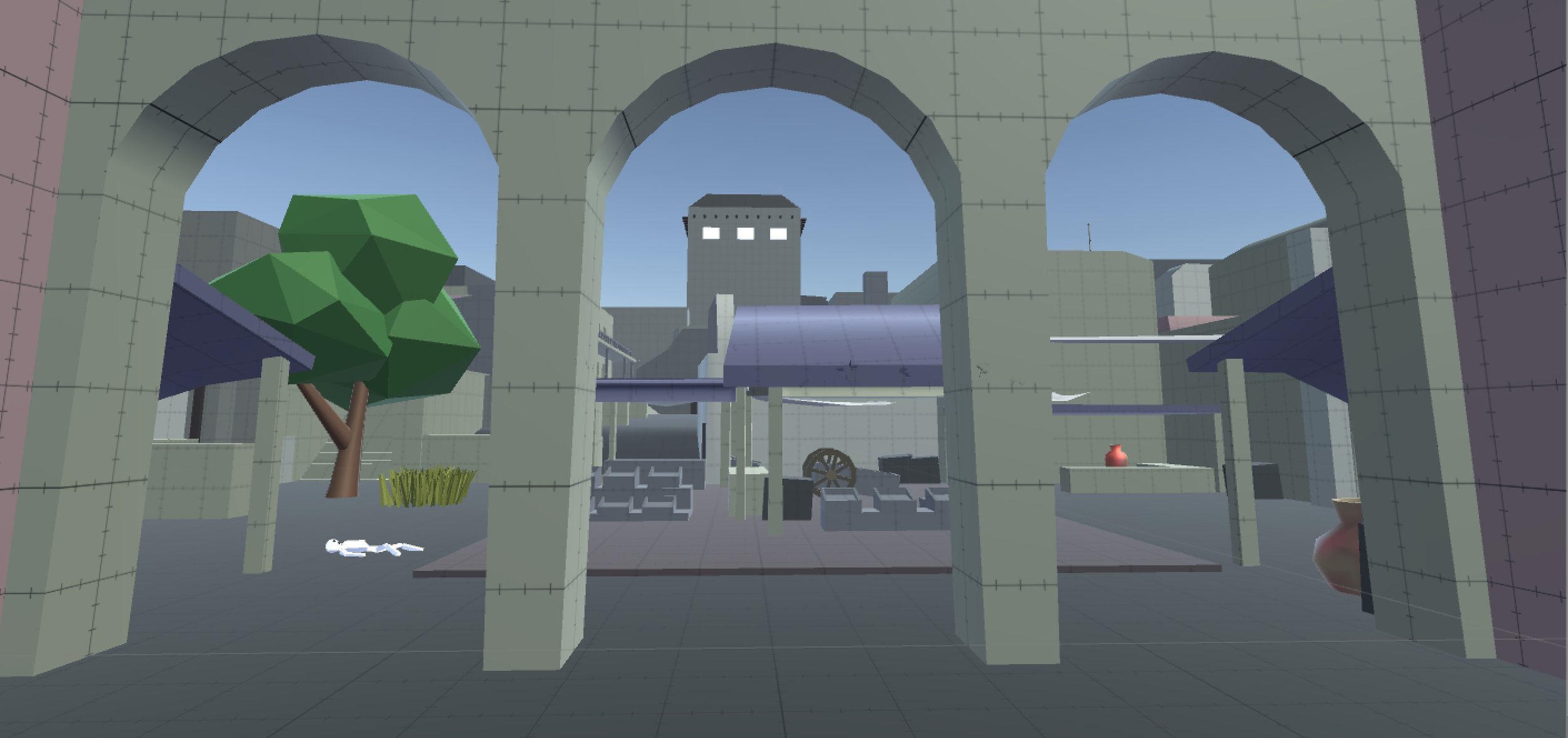

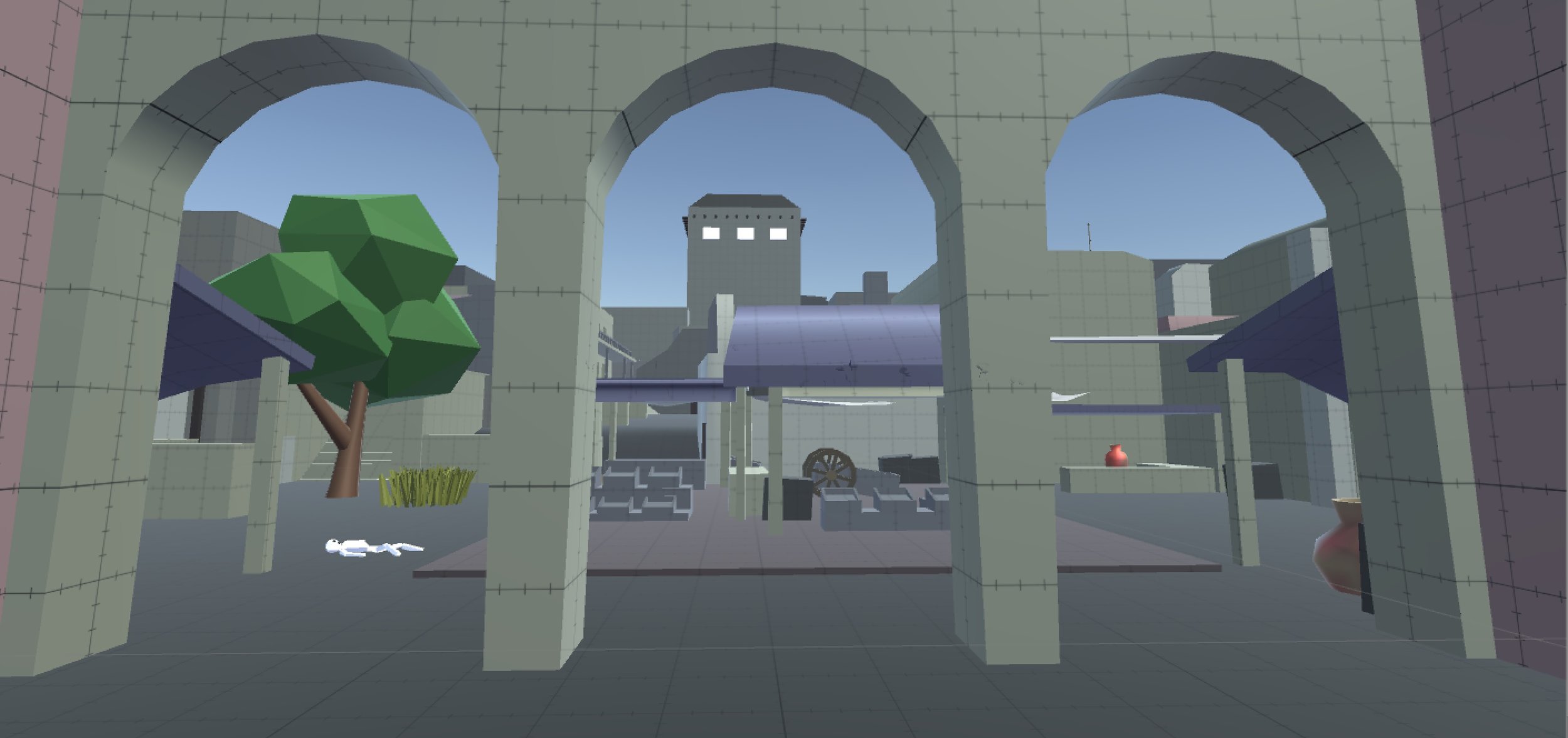

After passing through the city’s gates, the archways act as a framing device for the fort’s main tower. The tower represents a weenie, or a visual reference point that also represents the player’s goal and whets their desire to explore the space.

This idea originates from Seth Rogers GDC Talk, Everything I Learned About Level Design I Learned from Disneyland.

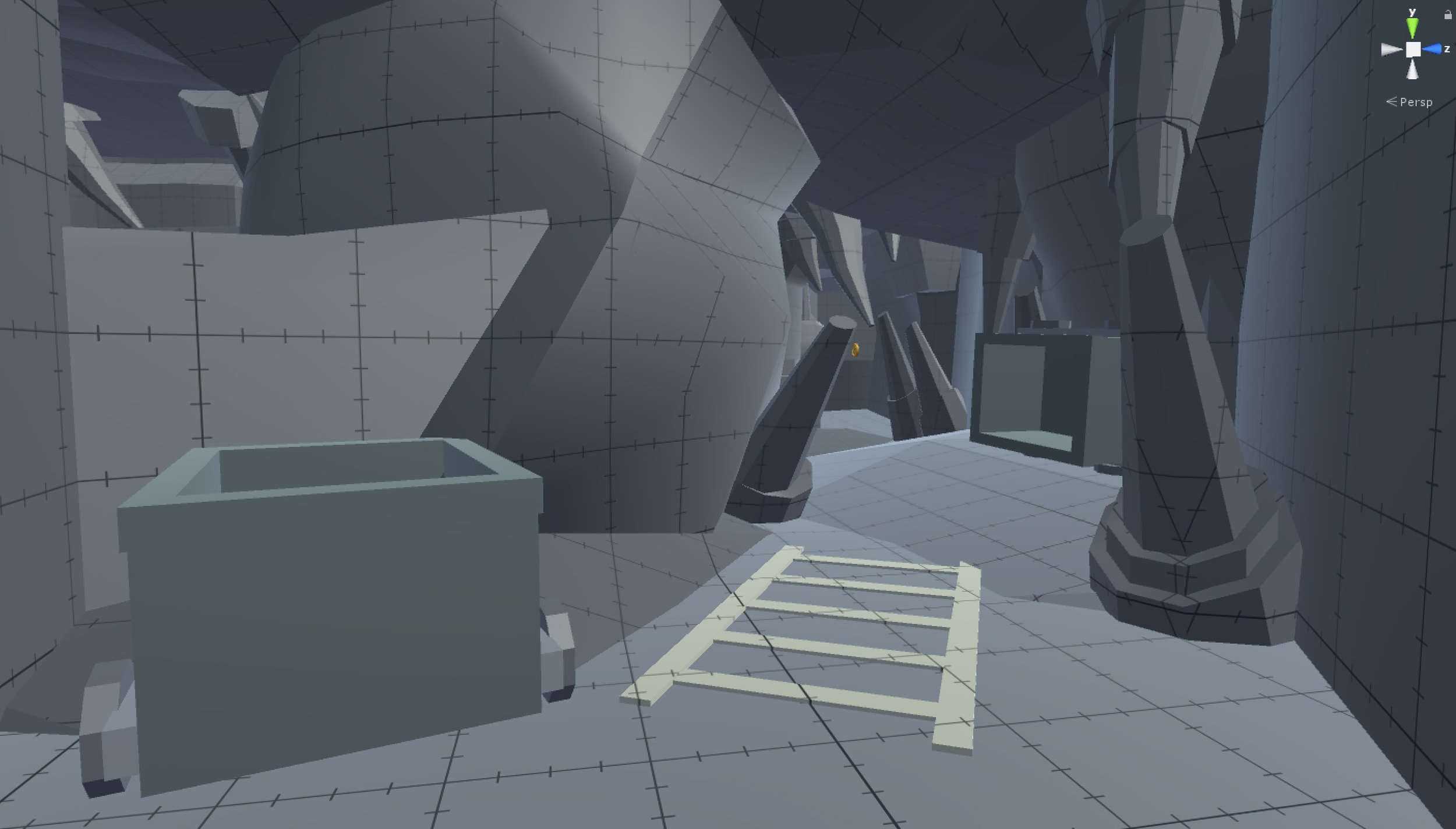

Story Context: After traversing the city and defeating the bandits stationed in the town’s fort, the cowboy enters an abandoned mine. He’s already seen darkness creep into his journey in the form of corpses left scattered throughout the town and hostile bandits, and now he must navigate a foreboding, abandoned mine in his quest for treasure.

Shape Language:

As opposed to the primarily rectilinear shapes of the town/fort area that the player has previously traversed, there are pointed stalagmites and stalactites lining the cave entrance. This shape language indicates danger.

mine carts dotting the path are rectilinear, man-made shapes. This shows that this area is a transitory space between the town and more dangerous and unpredictable caves ahead.

The mine cart tracks provide leading lines that guide the player’s gaze into the composition, drawing them into the space.

As the player navigates the mine, they travel through a fairly narrow tunnel. The purpose of this tight, narrow space, is provide contrast to the the large space the player is about to emerge into, making that space feel more impressive and intimidating.

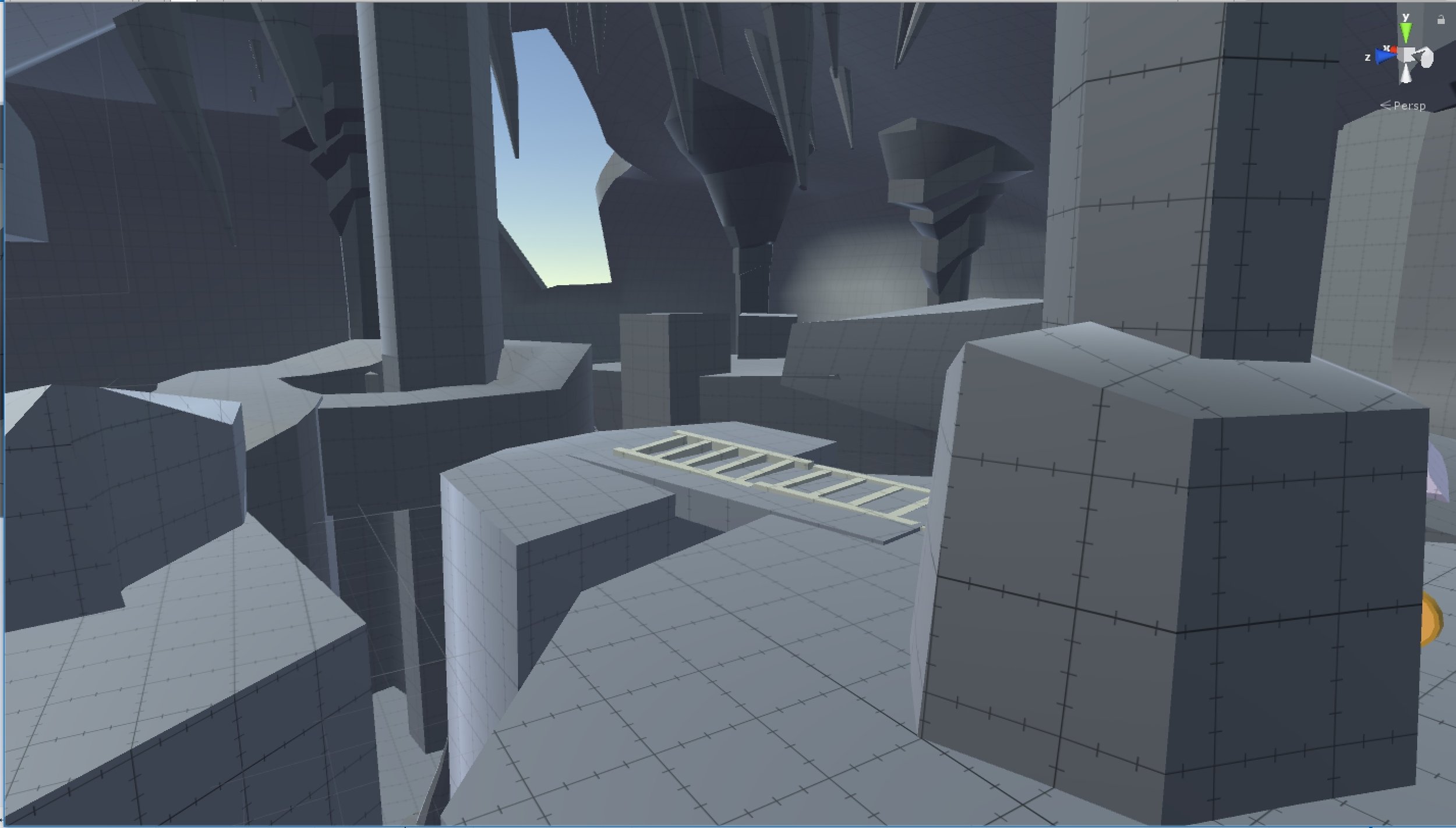

Story Context: After navigating a number of platforming challenges and environmental hazards, the cowboy emerges into a massive underground cavern. This large chamber represents the climax of the second exploration space before the cowboy emerges from the other side of the mines.

Shape Language:

The vertical rock columns draw the player’s vertically, to the floor and ceiling of the cavern emphasizing the height and size of the room.

Pointed, spiky stalagmites and stalactites coat the surfaces of this cavern. coupled with the height of the fall from the platforms that the player stands on, creates a tense, dangerous-feeling environment.

The platforms that the player can jump to to navigate through the space are relatively rectilinear in shape. The flat faces and hard lines and edges of these shapes afford utility to the player; these are shapes that the player can use to their advantage.

Story Context: After emerging from the mines and defeating the last of the bandits at their camp, the cowboy scales a group of small cliffs and finally recovers his mother’s treasure, concluding his journey.

Shape Language:

This area is meant to be a “hero space” that uses shape language to magnify the player’s feelings of accomplishment for completing the level and reaching their goal.

The one-point perspective of the space and the patches of grass to the left and right sides, lead the player’s eye directly to the treasure.

The wagons surround the chest, acting as a framing device

The majority of shapes in this space are rounded (bushes, trees). These provide contrast to the pointed shapes that the player encountered in the caverns. These are meant to emphasize the fact that the player has emerged from a dangerous space and is back in an area of safety

Triangular, sharp shapes are used as bumpers for the space, both on the edges and behind the treasure. The trees in the background act as a soft barrier, communicating that this is the end of the line and that nothing lies beyond.

Combat Space Design

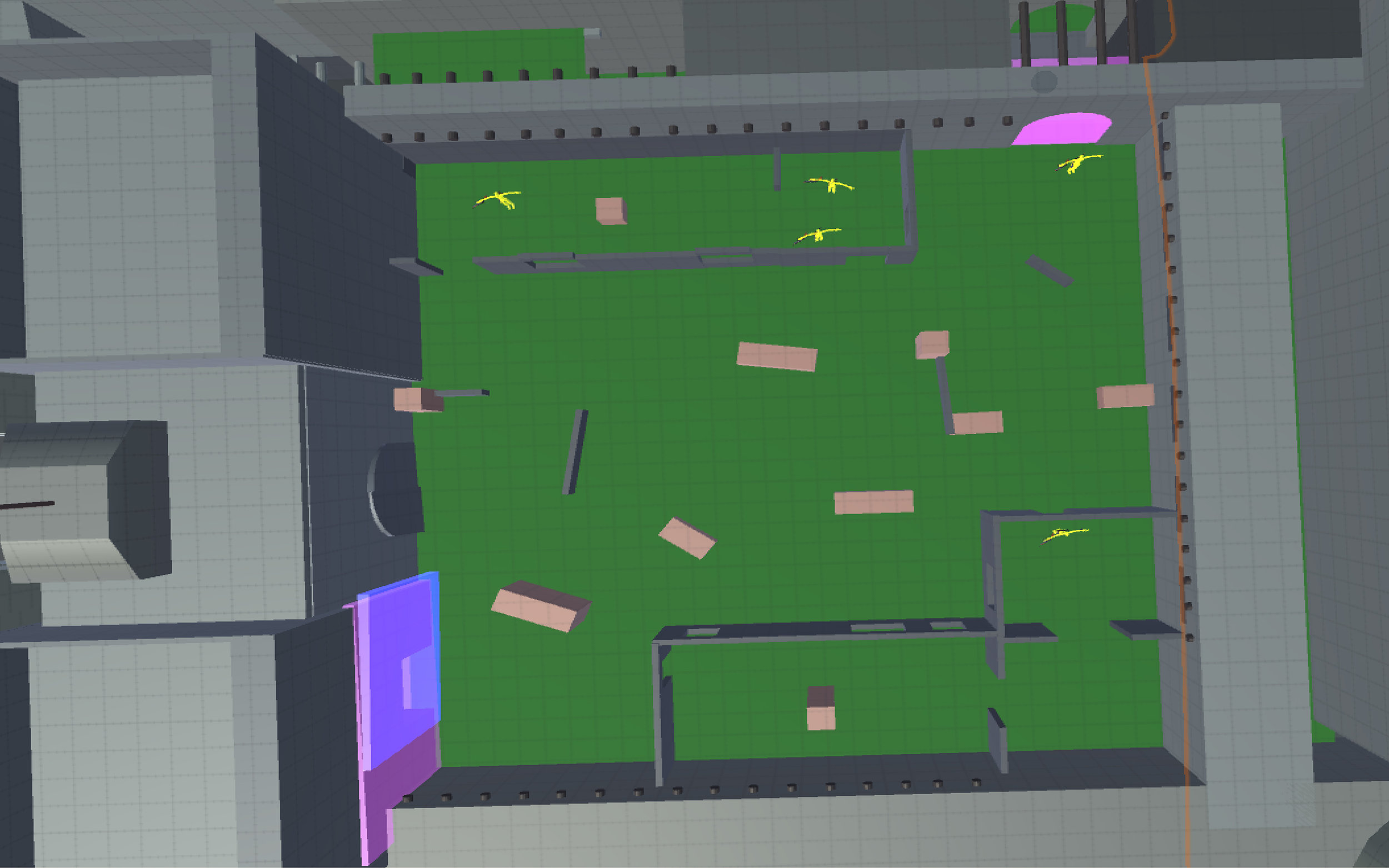

Below, I’ve outlined some of the considerations taken for the design of the 3 small combat spaces that comprise the fort area of the map.

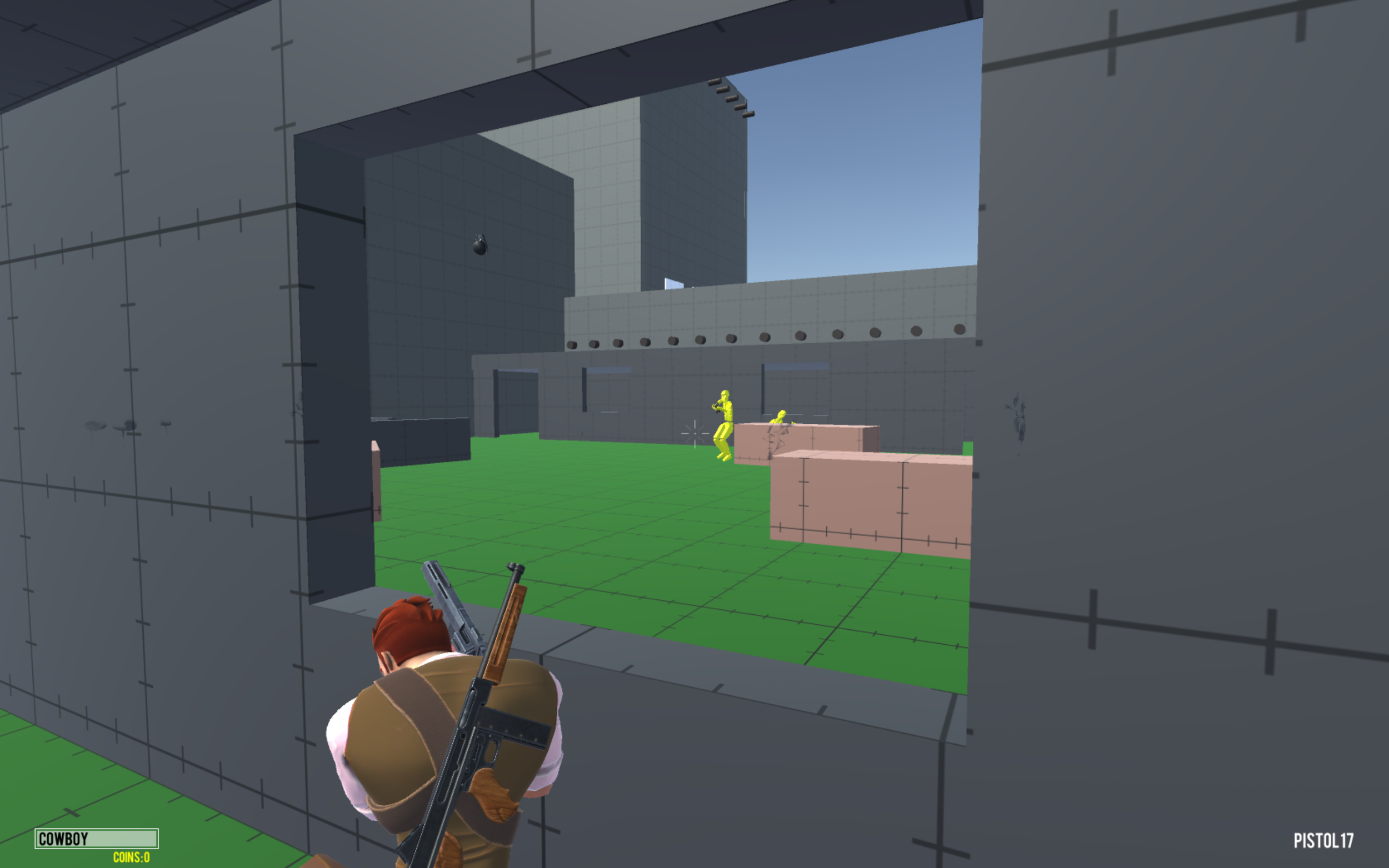

Small Combat Pt. 1

Valve- This is an example of one of the level’s valves placed prior to a combat space. The player must jump down to this cargo hold before entering combat.

This servers to separate the level's exploration and combat zones.

Player/Enemy Territory- The blue area represents player territory and the red area represents the enemy’s territory. At the beginning of the encounter, these represent the spaces that the player and enemies respectively can move around the space in relative safety.

The size and placement of these territories are based on cover placement and the area from which the player enters this area in addition to enemy spawn points. Cover Linkage also plays a role in determining these areas. This occurs when multiple pieces of cover are placed in such a way that they can be maneuvered between without exposing themselves from cover.

Combat Fronts- These are represented by the blue arrows. Fronts are the main lines along which gunfire is exchanged. Cover placement and orientation determine the location of these fronts.

Flank Routes- This space also includes a primary and secondary flank route. The purpose of flank routes are to allow the player or enemies to advance into enemy territory and attack the opposition from behind.

Due to the relative safety proved by the screen and backboard wall, the primary flank is the safer route, but there is also a secondary flank route (along the left side of the below image) that has cover linkage, but is the more exposed of the 2 routes. However, there is a refuge space at the end of the of this secondary flank (horizontal building along the top of the space), that is a good place for the player to hunker down and pick off enemies.

Small Combat Pt. 2 and 3

This space consists of 2 separate combat areas, the lower combat arena and the balcony.

When the player enters the lower combat area, they have the jump on the bandits, allowing them to sneak around the arena and take out an enemy or two before they’re alerted.

The upper, balcony combat arena features 2 adjacent flank routes that that the player can flow between as they move through the space, allowing them to escape enemies that they encounter in the close-quarters indoor area.

Districts, Edges, and Landmarks

The city area of the level is a nonlinear space with distinct districts and landmarks. Designing distinct districts, each with their own sense of personality adds believably and variety to the space and makes it more memorable for players. Each district is visually divided by an edge (usually taking the form of a gate or wall). Districts, edges, and landmarks also assist players with the process of cognitive mapping, or creating a mental visualization of the entire space. Successful cognitive mapping prevents players from getting lost and imparts a sense of mastery over the level.

The concept of cognitive mapping in relation to districts and landmarks is explored in urban planner Kevin Lynch’s book, The Image of the City.

Below I’ve outlined the various districts of the walled city area of my level:

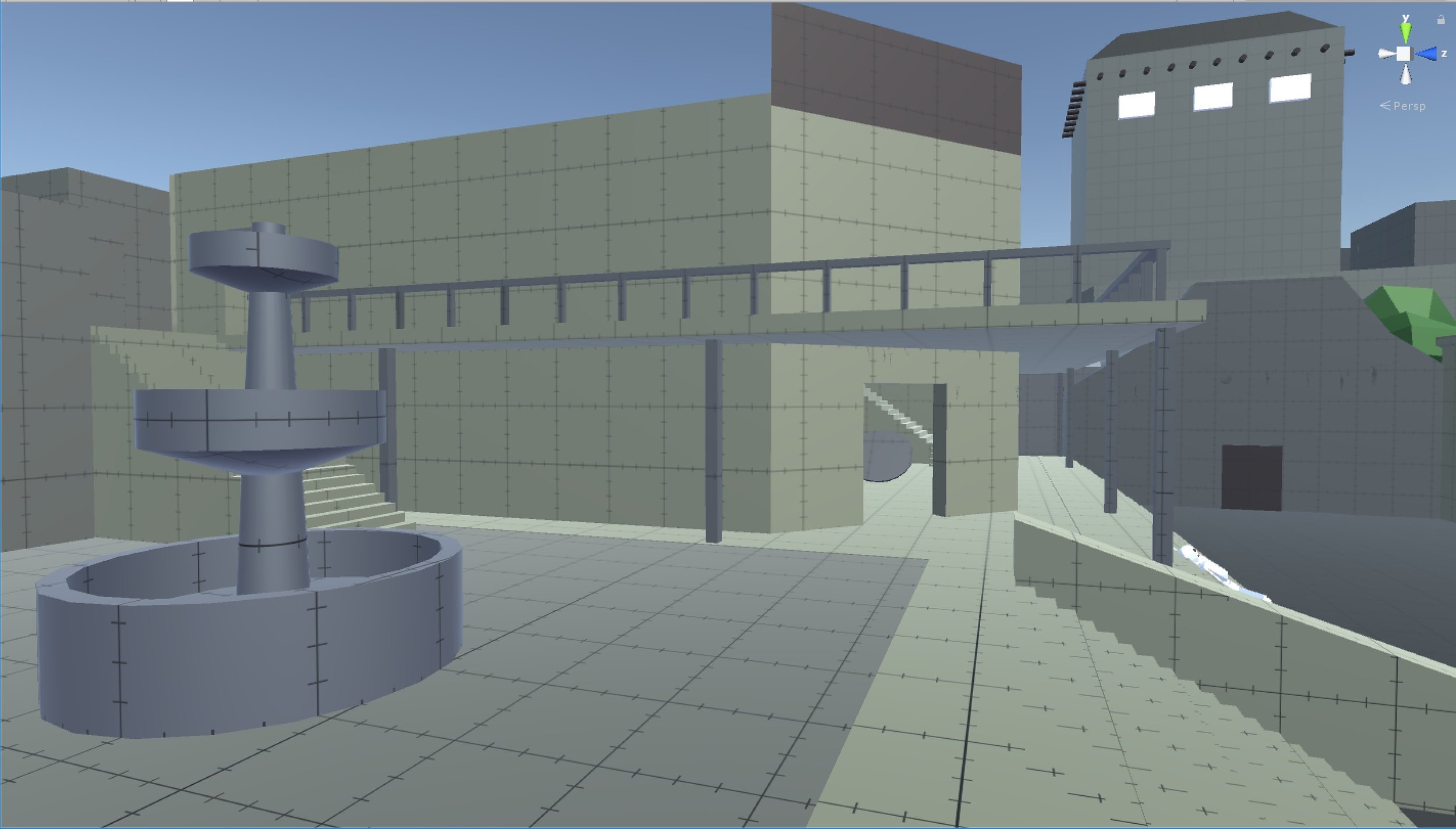

Commercial District

The central district is a commercial area that consists of an open air market and town square featuring a restaurant, saloon, and blacksmith’s shop.

Edge- The city entrance archways act as an edge that separates the commercial district from the surrounding wasteland.

Landmark- The fountain the town square (roughly in the middle of the district is a recognizable landmark to help players navigate.

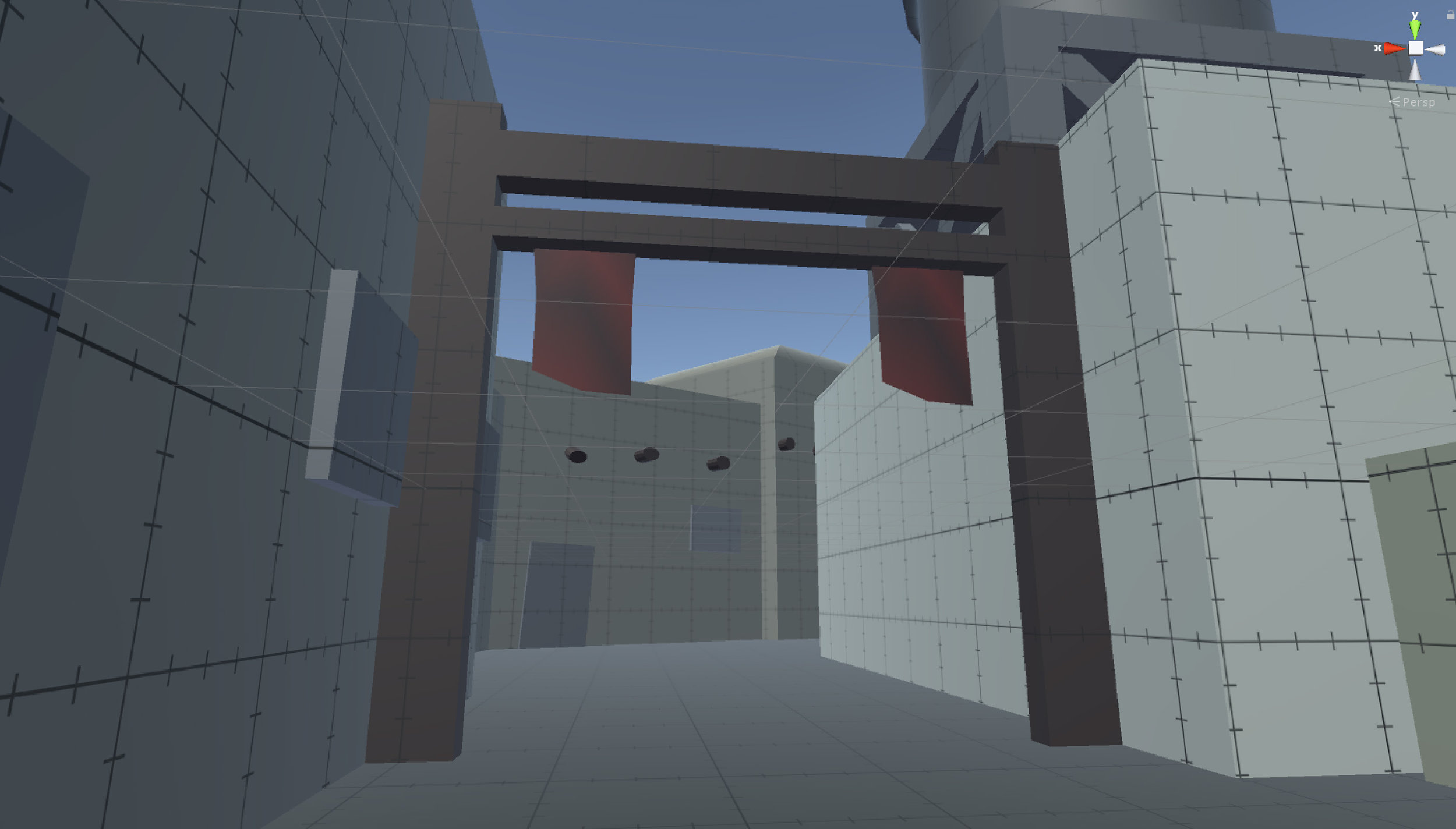

Slums

The slums reside to the left of the commercial district. This area is defined by it’s tight alleyways. Overhead beams serve to make the space feel more confined by providing an overhead roof plane to sections of this primarily outdoor area. The slums also feature overgrown trees and foliage, broken, uneven steps, and various pieces of debris out in the open.

Edge- The slums are separated from the commercial district by wooden gates with hanging banners.

Landmark- There’s a small, pauper’s graveyard tucked away at the end of the slums corridor. This area contributes to the environmental storytelling of the area, houses a hidden collectible, and acts as a landmark to help the player map the district.

Affluent Residential District

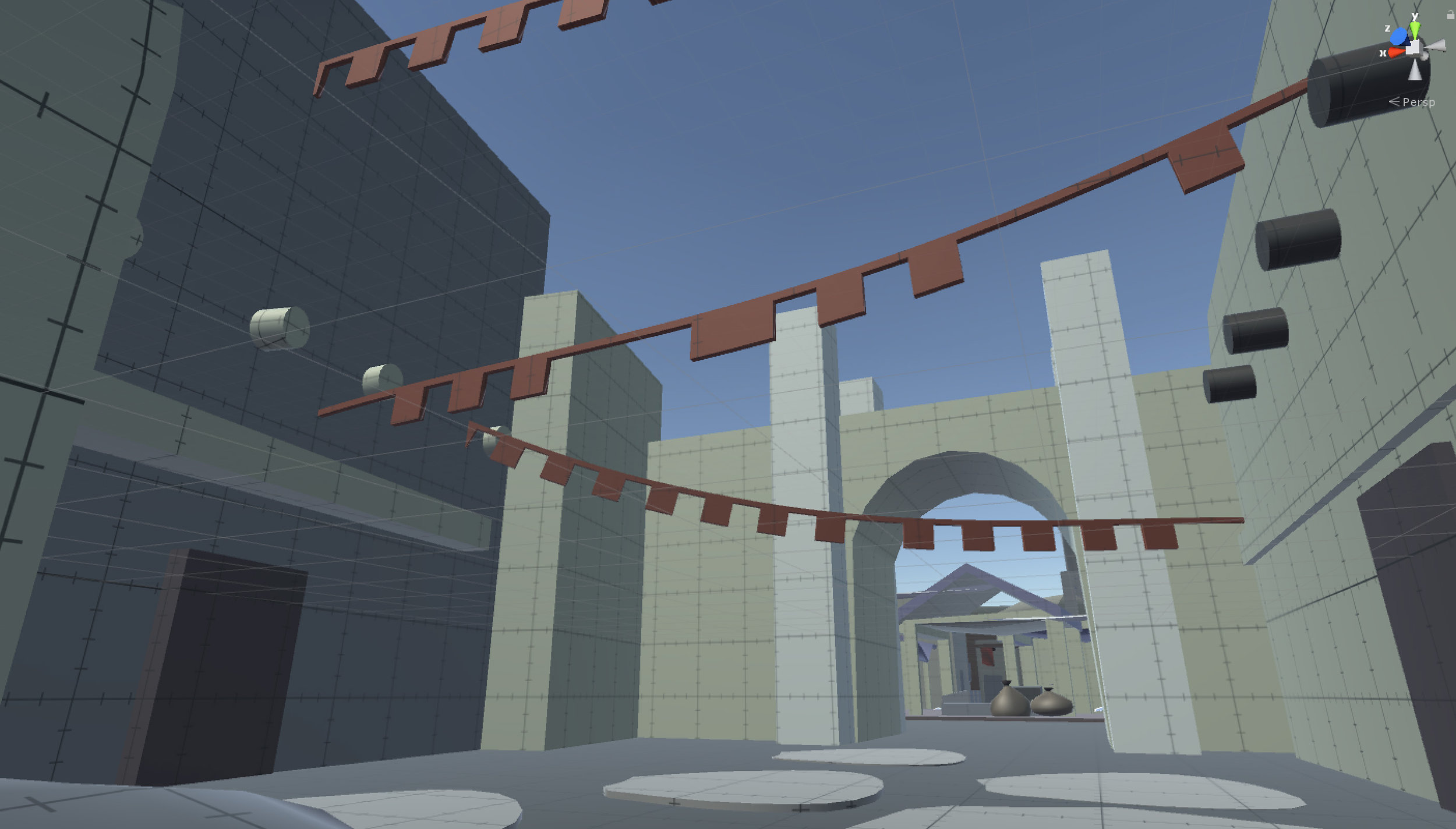

To the right of the commercial district resides a more affluent residential area. This district is defined by it’s hanging flags that crisscross the street, paved, stone roads (in contrast to the dirt roads of other districts), wide streets, and damage caused by an apparent fire.

The edge to this district is a thick, stone gate that stems from the main city wall.

Landmark- several destroyed buildings reside in the corner of this district. This landmark, complete with corpses buried in the rubble is intended to memorable to players and provide contrast to the more upscale environs that surround it.

Courthouse and Gallows

The courthouse and gallows district resides at the top of the city. This area is defined by the mass execution that apparently took place here backgrounded by the imposing courthouse structure.

Edge- The courthouse is separated from the commercial district by a stone gate.