Left Unsaid

Description: Left Unsaid is a narrative adventure game built with the strengths and weaknesses of VR in mind. The game is focused on immersing players in a single space in which a narrative is communicated to them via environmental storytelling.

Platforms: Oculus Rift, HTC Vive

Team: 4-person team

Type: Academic (Carnegie Mellon University with mentorship from Oculus Story Studio)

Role: Game Designer/ Environment Artist

Core Responsibilities: Level Design, Environment Art, Systems Design

Tools: Unreal Engine 4, Maya

Available for download on Itch.io

Plot Overview

Using a time machine left abandoned by it’s creator, the player explores the memory of an abandoned manor. Through environmental storytelling, the player uncovers a narrative of a relationship that slowly fractured over the course of several decades.

Videos

Behind the Scenes

Full Gameplay

Please excuse the shaking hands. It’s not a technical issue. Our producer Brian (who recorded this footage) had low blood sugar. If you were worried, he ate lunch afterward and felt better.

Design

Environmental Design

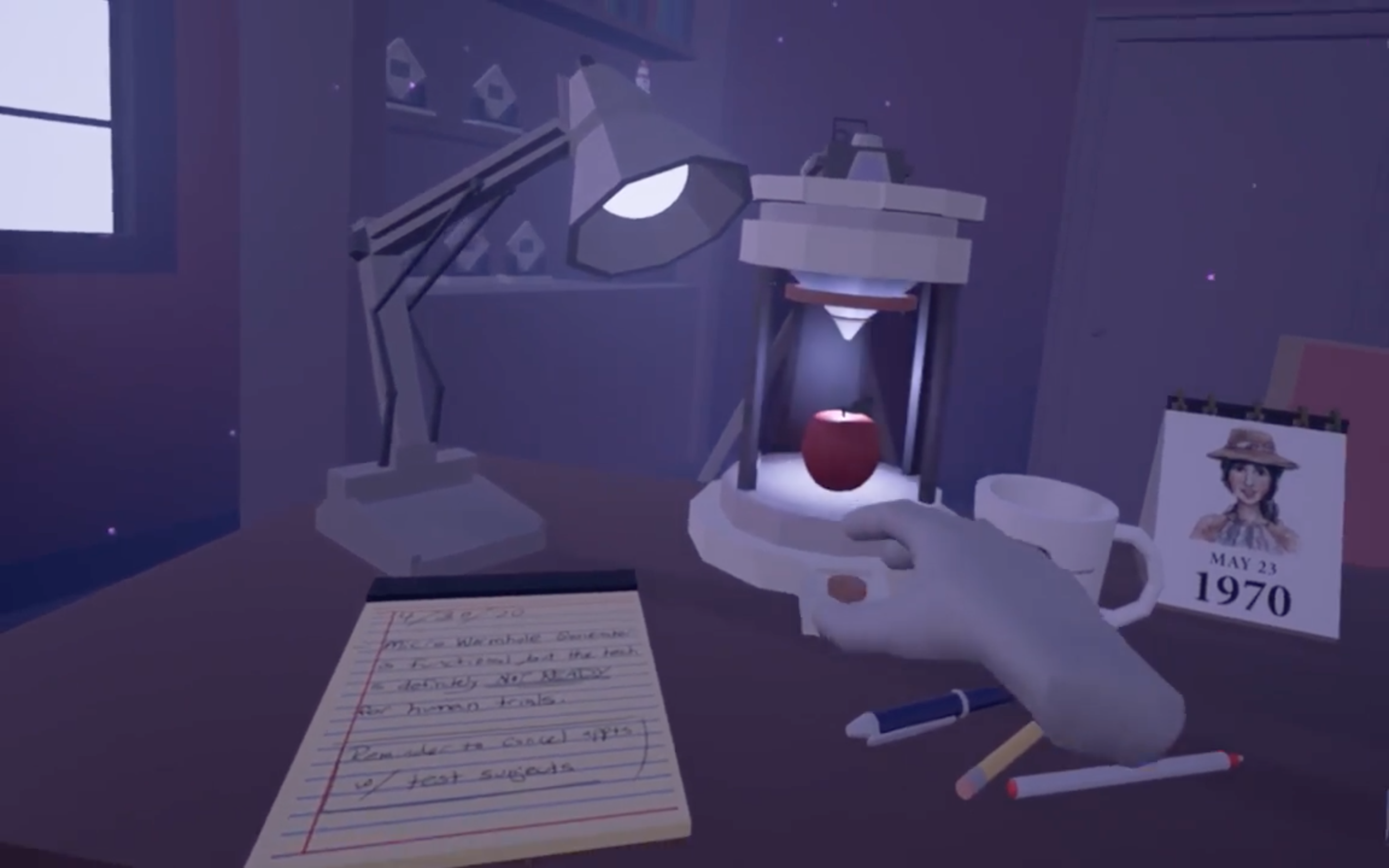

Left Unsaid is a period piece that takes place in 4 different time periods (1956, 1970, 1977, and 1985). Our goal was to use environmental storytelling to reflect both the time period, and the state of the 2 primary characters’ relationship with one another.

A page of my game design documentation detailing the overarching story structure. The user starts the experience 1985, then travels back into the world of memory using Edward’s machine. They first explore 1956, then 1970, then 1977, before returning to 1985 for the finale.

Our environmental art process consisted of 4 phases- Inspiration gathering, concepting, layout design, final asset creation/ placement. This process allowed us to establish an authentic mid-century look for Edward’s office (with changing accouterments based on the time period). Edward’s inventions were heavily inspired by IBM technology from the 1960’s and 70’s, Our team took a research trip to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, CA to view some of these computers up-close and gather reference images.

Level Design Using VR Affordances

Like many VR games, Left Unsaid allows users to interact with virtual objects with motion controllers. This interface provides a less abstract means to interact with the world than a typical gamepad or keyboard and mouse setup. Because of this fact, we paid careful attention to the concept of affordances (the relationship between the perceived and actual properties of an object) in our level design.

The Memory Machine’s plug and retina scanner are examples of interactable objects that communicate their functionality through visual design.

Environmental Storytelling

The main mechanics of Left Unsaid is finding special, “infused” objects, holding them to your ear to listen to the audio memory that they contain, then placing them in the machine to extract said memory (it is used as means to calibrate the machine as it takes the user forward in time.)

There are 3 major object types in the game:

Critical Path Objects- These are the objects with audio memories attached. The player must find all of these to progress and ultimately finish the game. These objects (both visual design and audio memory) constitute the key plot points necessary to understand the story.

World Building Objects- These objects add texture to the story and setting if the player is paying attention, but aren’t strictly necessary to understand the plot

Filler- Staplers, pens, etc. These add believably to the setting, but are insignificant to the story.

Below is an example of my favorite (and the most elaborate) of the World Building Objects- Edward’s micro wormhole generator. This object ties into the character’s obsession with using science to reach other worlds, as well as his neglect of his grounded, worldly responsibilities. There’s also a joke there if you read what Edward’s written on his notepad and that observe the effects of the wormhole generator.

In Left Unsaid, we worked to design and implement a sense of “pointless interactivity.” This idea, in the context of our game, means that it is possible to interact with everything in the world that could reasonably be picked up and interacted with, not only objects related to the critical path. This is important for building a sense of immersion, a major design goal of Left Unsaid, and also a general strength of VR.

Creating Our Progression Structure

In our early iterations of Left Unsaid, many players would pick up every object in their vicinity in quick succession to find the critical path objects necessary to advance through the game as fast as possible, quickly discarding everything else. This wasn’t the intended experience.

To fix this issue we introduced a gating structure within each time period in which the player needs to solve small puzzles in the environment to find each critical path object. Laying out these narrative breadcrumbs had a couple of positive effects on the experience; players slowed down and examined the environment more closely and as a result, absorbed more of the story. It also allowed us to introduce the critical path objects in a particular sequence, giving us greater control over the pacing of the game’s narrative beats.

Below is one example of this type of structure:

Post-Mortem

At the end of the project, the team wrote a long-form analysis of our game, in which we break down the development process in detail and consider both our success and and our failures in the areas of design, art, tech, and production. Read the post-mortem here.